Pollution has long been shown to have disproportional impacts on minority communities, especially in urban centers, but an innovative review from Colorado State University shows how an oft-overlooked source—noise pollution—affects city neighborhoods that were once “redlined.”

In the United States, redlining describes now-banned discriminatory housing policies that date back nearly a century and once limited access to housing loans and other services. The policies that targeted communities of color then left an imprint that exists today.

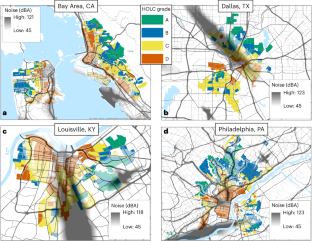

“Starting in 1933, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation assigned grades to neighborhoods based on race and wealth,” explains the research team, led by assistant professor Sara Bombaci of the university’s Department of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology.

“Grade A neighborhoods were wealthier and whiter, while red lines were drawn around grade D neighborhoods where people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds lived. Redlining was outlawed in 1968, but decades of divestment in these neighborhoods caused enduring disparities.”

Bombaci and a team of acoustic ecologists actually were focused on the urban noise impacts to wildlife, but their work involved looking at how urban noise was distributed across the historical racial divisions that were rooted in the redlining policies of 83 U.S. cities.

Their work, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, found that grade D neighborhoods experience 17% higher maximum noise levels today than grade A neighborhoods do. Further, the grades C and D neighborhoods more often have urban noise levels above the level known to cause human health impacts. Among them are an elevated risk of heart disease and stroke, stress, and hearing loss.

“This is directly linked to structural racism,” Bombaci said. “There’s a clear signal that ties directly to whether these communities were redlined.”

Noise levels stress wildlife, too, and can change reproductive behavior or make certain species more vulnerable to predators. “We need to be thinking more about how these systemic injustices and problems are manifesting to shape ecology and evolution,” said Bombaci, whose study is believed to be the first to examine noise inequity in redlined communities.

She notes that practical use of the information might include adding noise reduction considerations when planning to improve access to parks and green space in these historically marginalized communities. Noise could limit the continued presence or return of wildlife in the urban setting, too.

“If we’re adding green space without mitigating impacts of noise, we might not be fully recognizing the benefits of these green spaces,” she said.

The study paper notes “a growing body of literature documenting the relationships between redlining and the inequitable distribution of environmental harms and goods, green space cover and pollutant exposure.” But another new study from the U.S. city of Los Angeles warns that White neighborhoods are starting to lose their historic advantages in an increasingly hot climate.

Wealthy, demographically White neighborhoods still benefit from more trees, less pavement, and cooler temperatures, but the protective effects were only about 58% as strong in 2020 as they were in 1990, according to a study led by botany experts at the University of California – Riverside. The Los Angeles data was published last month in the journal Urban Climate.

There’s no escape from heat and drought, but the UC study makes clear that environmental impacts still reflect inequities. “Hispanic communities faced disproportionate warming when compared to their White counterparts,” the authors conclude.

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (30)