China’s illegal wildlife trade has been the source of untold suffering for both animals and people attached to trafficking operations, but now it is implicated in the evolving coronavirus threat that has sealed off the city of Wuhan and spread to other nations.

George Fu Gao, the director general for China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention, said Wednesday that the new 2019-nCoV virus originated from wild animals illegally sold at a seafood market in the city of some 11 million people. The market is less than a kilometer from Wuhan’s high-speed railway station, a high-traffic area in and out of a city that is now effectively quarantined as many of its citizens seek health care.

There’s much to learn about the outbreak, and the World Health Organization delayed a decision on whether to designate a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) while gathering more information. Yet a new research paper from five Chinese scientists, published rapidly by the Journal of Medical Virology in light of the emergency, points to a specific species.

“Many patients were potentially exposed to wildlife animals at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where poultry, snake, bats, and other farm animals were also sold,” the scientists said. “Our findings suggest that snake is the most probable wildlife animal reservoir for the 2019‐nCoV,” they added, basing results on an isolated glycoprotein they believe is a pathway in the animal-to-human transmission.

It’s similar to the link with bats that was implicated in the 2003 SARS coronavirus epidemic, which spread to 26 countries and involved more than 8,000 cases once it progressed to human-to-human transmission. A second paper suggests a potential bat origin for this new virus too.

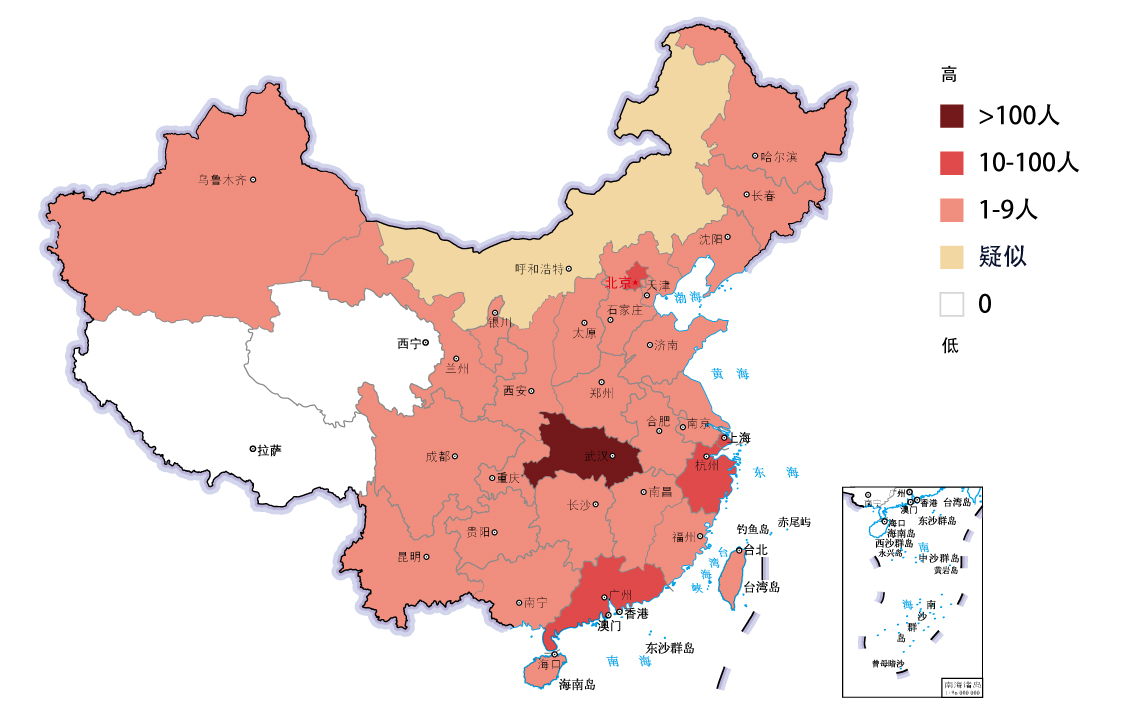

While public health authorities think that 2019‐nCoV is not yet as serious as SARS was, Gao warned that the virus was adapting and mutating, making it harder to control. The severity of illness and rate of spread are alarming: A real-time reporting site from Lilac Garden, a forum for Chinese medical professionals, listed 639 confirmed cases and another 422 suspected cases as of 12 a.m. local time on Friday, with 17 fatalities.

Most of the cases are in the interior Hubei province but others are spread across China’s populated east, the coastal cities including Beijing and Shanghai, and the adjacent Macau, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

What’s even more sobering to global health officials is the spread to other nations. Thailand and Japan were the first to confirm cases originating in Wuhan. The United States and South Korea were next. Singapore has a new one. Russia, Brazil, Scotland, France and the Philippines are investigating cases. Mexico says it is monitoring the case of a a 57-year-old university biotechnology researcher who returned from Wuhan some 12 days ago.

Those nations without reported cases, from South Africa to the United Kingdom, are taking precautions. The European Union’s Center for Disease Prevention and Control issued an updated assessment on Wednesday, warning that the potential for impacts from 2019-nCoV remains high and further spread of the virus is likely.

“The original source of the outbreak remains unknown and therefore further cases and deaths are expected in Wuhan, and in China,” the EU said. Travel patterns may mean cases in EU nations, though “there are considerable uncertainties in assessing the risk of this event, due to lack of detailed epidemiological analyses.”

As the world waits to learn more, the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak already serves as a breathtaking example of how connected the world has become, and how the well-being of humans and animals is so clearly intertwined. China is by no means the only nation that has failed to get a handle on an illegal wildlife trade that officials believe is at the root of the problem. It’s also not the only nation affected by the consequences.

Did you like it? 4.4/5 (28)