The biodiversity commitments made at COP15 in Montreal leave much room for optimism, with delegates agreeing to goals of protecting 30% of global land and water systems by 2030 in order to guard against species loss. What there’s less room for is delay, according to the results of new scientific models that suggest cascading extinction patterns are already unavoidable.

The models were developed by European Commission scientist Dr. Giovanni Strona, University of Helsinki, and Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University. They relied on one of Europe’s most powerful computers to demonstrate, for what they say is the first time, just how interconnected these species extinctions are likely to become.

“Think of a predatory species that loses its prey to climate change. The loss of the prey species is a ‘primary extinction’ because it succumbed directly to a disturbance,” explains Bradshaw. “But with nothing to eat, its predator will also go extinct…a ‘co-extinction’. Or, imagine a parasite losing its host to deforestation, or a flowering plant losing its pollinators because it becomes too warm. Every species depends on others in some way.”

He added that by 2100, these co-extinctions will raise the total extinction rate of the most vulnerable species by up to 184%.

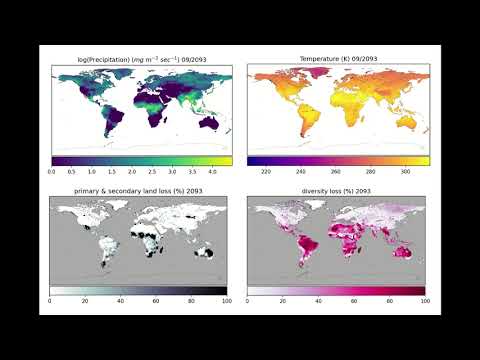

Bradshaw and Strona arrived at the numbers by creating complex simulations of Earth to explore more than 15,000 food webs, and better understand the mechanisms behind these connections and the impacts of climate change and land-use patterns on biodiversity.

What they concluded, in a paper published last week in Science Advances, is that the planet will lose an estimated 10% of its animals and plants overall by 2050. The loss rises to 27% by 2100.

“Essentially, we have populated a virtual world from the ground up and mapped the resulting fate of thousands of species across the globe to determine the likelihood of real-world tipping points,” Strona said. “We can then assess adaptation to different climate scenarios and interlink with other factors to predict a pattern of coextinctions.”

Strona said the work leaves no doubt that climate change is driving extinction. The study authors note that if lower global carbon emissions are achieved, limiting global warming to less than 3℃ by 2100, biodiversity loss could be held to 13% of species. Some loss is already unavoidable.

“Children born today who live into their 70s can expect to witness the disappearance of literally thousands of plant and animal species,” Bradshaw says, “from the tiny orchids and the smallest insects, to iconic animals such as the elephant and the koala … all in one human lifetime.”

Did you like it? 4.7/5 (20)