For most people, especially those living in urban areas, “biodiversity” is an abstract concept. It’s a term they may hear used by biologists and environmentalists but one that does not seem to have any relevance for their own lives. How wrong they are.

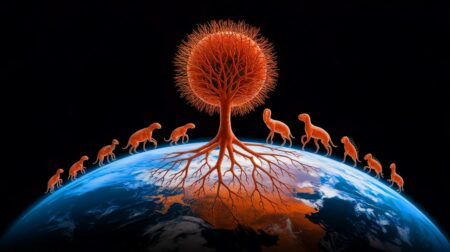

The loss of biodiversity affects us all. And we are losing it at a rate unprecedented in the entire history of the human species. Worse: we are the cause of it. We have been polluting our oceans and fishing them as if there was no tomorrow. We have been cutting down forests and hunting myriad wild animals mercilessly. We have been changing the climate by pumping vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The planet, which not long ago was teeming with life, is now losing species at extraordinary rates. For vertebrates alone that rate is up to 114 times the historical average. In other words, species are dying 114 times faster than they would have done if we had left them to their own devices in their undisturbed natural habitats. But of course we have not let them remain undisturbed. In fact, few are the natural habitats that have not been badly affected in some form or other by human activity.

“Our activities are causing a massive loss of species that has no precedent in the history of humanity and few precedents in the history of life on Earth,” said Gerardo Ceballos, a professor of conservation ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico and a visiting professor at Stanford University.

And the loss of even a single species, iconic or not, can have wide-ranging consequences for entire ecosystems. That’s because each species fills a specific niche in food chains, thereby playing a specific role. Lose that species, and you risk upsetting the fragile equilibrium of an ecosystem.

And we aren’t just losing single species. We are losing scores of them at once. The situation, owing to human-induced mass extinctions, has become so bad in many ecosystems around the planet that they may well be on the verge of collapse, say the authors of a study published in the journal Science.

“This is the first time we’ve quantified the effect of habitat loss on biodiversity globally in such detail,” the study’s lead author Tim Newbold, a researcher at University College London in the United Kingdom, said, “and we’ve found that across most of the world biodiversity loss is no longer within the safe limit suggested by ecologists.”

And that, needless to say, should concern all of us for a variety of reasons. Most human crops rely on natural pollinators – insects, birds, bats, small mammals – and many of them are barely hanging in there in the face of massive habitat loss, pollution and other human-made hazards.

Our protein sources like fish are, too, fast becoming depleted because of relentless overfishing in the world’s oceans. With lower levels of biodiversity also come higher rates of disease. The loss of natural habitats often means the loss of natural barriers to debilitating diseases. Then there is of course the loss of clean air and clean water. We lose natural air-cleaning agents when we cut down trees and we lose clean water when we pollute our rivers, lakes and seas.

By continuing to degrade ecosystems and by continuing to decimate species in them, we are also undermining their ability to naturally heal themselves. With that we lose a natural “insurance” against environmental disasters. “Biodiversity insures ecosystems against declines in their functioning because many species provide greater guarantees that some will maintain functioning even if others fail,” the so-called insurance hypothesis explains.

Healthy biodiversity allows for ecosystems to respond effectively to disasters like fires, droughts and floods. That is because if, say, a single species of reptile, insect or mammalian species goes extinct in a natural disaster, an ecosystem with many other reptiles, insects or mammals is far more likely to rebound than one without such a rich diversity of “back-up” species.

But perhaps most importantly, by losing biodiversity we also lose much of nature’s wondrous bounty – and irreplaceably so. Imagine a world where tigers, rhinos, orangutans and myriad others species large and small can be found only in the relative safety of zoos and fenced-off sanctuaries. What an impoverished world that will be! Yet that is exactly the world we are creating.

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (25)