Participants at the COP15 summit on desertification and deforestation, which opened in Côte d’Ivoire this week, are focused on action to limit climate impacts in places like the hard-hit African continent. Yet there’s also rising concern for forests in nations that may be closer to home, France among them.

The National Forestry Office (ONF) says France has lost more than 300,000 hectares of public forests since 2018. Scientists attribute much of the damage to climate change, which is driving drought conditions that stress trees, making them more vulnerable to insect damage and leading to more frequent wildfires.

There doesn’t appear to be an end in sight. Météo France said Sunday that precipitation is down 35% across the nation, with 10 districts in an alert status. That places additional challenges on trees, as well as drinking water resources and agriculture.

“Almost all territories are affected,” says ONF’s Olivier Rousset of the ongoing forest conditions. “All species are concerned, hardwoods and softwoods. The first affected are those that need the most water, such as beech, the emblematic species of our forests.”

France is losing other trees too. In the forest of Tronçais, a department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, between 15% and 20% of trees in the ancestral oak forests die before reaching maturity. Spruce trees are hardest hit in Grand Est, in the northeast part of the country.

Rousset, the deputy director general at ONF, says adaptation is key because the forests can no longer keep up with these changes on their own. His agency seeks to minimize ecological impacts, including carbon sequestration and habitat loss, but also the economic shifts for forest-based industries.

Foresters will need to consider other tree species and anticipate the zones where trees will survive in the climate of the future, often by using tech tools like the ClimEssences app.

“We are returning to the old vocation of public foresters: to intervene more, when necessary, relying on natural processes and, if necessary, resorting to planting,” says Rousset.

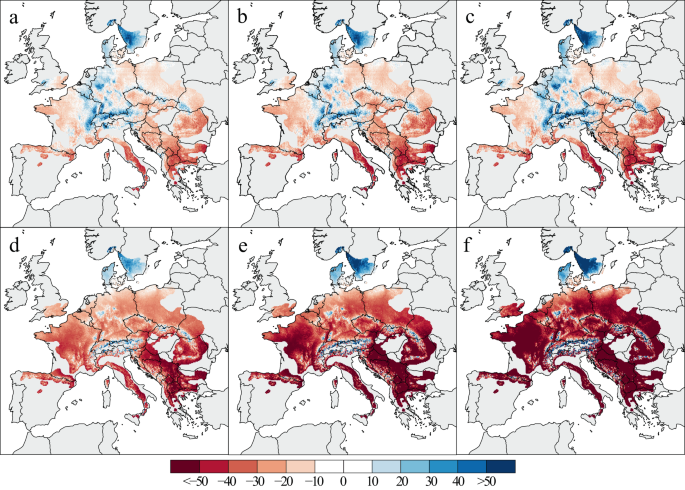

That may mean fewer beech trees, which are especially sensitive to climate impacts across Europe. Their growth is most severely curtailed across the southern zones where the tree grows, but one recent study published in the journal Communications Biology finds widespread declines across Europe.

That research, conducted by scientists in Germany and Spain, looked at the beech species patterns in Europe from 1955 through 2016 and found declines everywhere except for Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and high mountain elevations.

When they modeled the projected losses in various climate scenarios in the future, they found beech growth reductions in southern Europe of up to 30% by 2050, even in the most optimistic climate scenario. That includes parts of France and Germany.

“The projected 21st century growth changes across Europe indicate serious ecological and economic consequences that require immediate forest adaptation,” the authors conclude.

The ONF is working on these adaptation measures, including assisted migration. For the past 10 years, they’ve conducted an experiment in Grand Est, where 7,000 beech and oak trees from the south of France are planted to see how well they adapt and reproduce in the adjusted climate.

The ONF foresters won’t know the answers to those questions for another 70 years.

“We now have to consider different management in an ‘uncertain’ context,” says Xavier Bartet, deputy director of ONF research. “The task may seem daunting because we really need to rethink our forest management.”

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (20)