Plastic waste has reached colossal proportions around the planet and dealing with it will require creative solutions. Among such solution is a scientific quest to harness the powers of certain microbes to digest components of plastic waste.

Enter lowly fungi. These microorganism can wreak havoc with plants and other lifeforms, yet they can also come to the rescue now with plastic waste, according to an international team of some 100 scientists. In a special report, published by Kew Botanical Gardens in London, the scientists explain that certain types of fungi can degrade polyurethane within weeks.

This plastic-busting potential of fungi aspergillus tubingensis, a form of soil fungus, was discovered last year by a team of scientists from China and Pakistan at a waste disposal site in Islamabad. During their trials in the laboratory, the scientists found that the fungus grows on the surface of plastics, where it secretes enzymes that break the chemical bonds between plastic molecules, or polymers, within a matter of weeks, which is to say a lot faster than it would take plastic to decompose naturally.

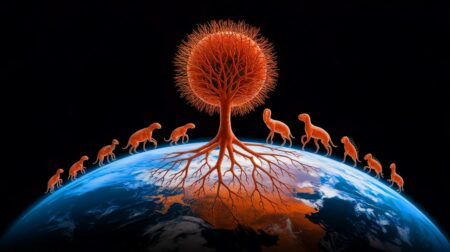

The planet has an estimated 3.8 million species of fungus, only 144,000 of which have been named, so a whole world of wonders may still be waiting to be discovered. “There is this hidden, mysterious kingdom that is underpinning the majority of life on earth,” Dr. Ilia Leitch, a senior scientist at Kew Gardens, said. “We just don’t know enough about them.”

Nor are fungi the only microorganisms that have been found to have the capacity to chow down plastics.

Recently a team of researchers at Kyoto University reported in an article in Science magazine that they have isolated a strain of bacteria that can “break down and metabolize plastic.” That’s right: they have found bacteria that love to chow down plastic.

The Japanese researchers spent five years examining 250 samples taken from a plastic-recycling facility in the Japanese city of Sakai before they isolated a new species of bacteria – Ideonella sakaiensis – that could live on the most common type of polyester, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which is widely used in bottles, containers, packages, synthetic clothing and other consumer products.

It isn’t the first time that plastic-eating microbes have been discovered and hailed as the potential new heroes of our rubbish-strewn planet. During an expedition to the Amazon a group of researchers from Yale University in the US discovered a fungus, Pestalotiopsis microspora, that, too, can break down polyurethane, a commonly used industrial plastic. They reported their findings in a 2012 article in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology. However, the fungi would be hard to cultivate at an industrial scale, which would make them unsuitable for the large-scale disposal of plastic waste.

Not so with the recently discovered bacteria. All the Japanese scientists needed to do was leave the bacteria in a warm jar along with polyethylene terephthalate and some other nutrients, and within a few weeks they disposed of all the plastic without a trace.

Plastics have been around for 70-odd years and that has been enough for Ideonella sakaiensis to have evolved the ability to produce an enzyme for breaking down and digesting PET. Better yet, the researchers have been able to produce the same enzyme on their own for breaking down PET even without the help of the bacteria.

Needless to say, all this is good news. Some 300 million tons of plastic are manufactured each year around the world, and much of it ends up in landfills, garbage dumps and floating around in oceans. Traditional methods of recycling plastic involve melting and reshaping old plastics into new products, but the newly found bacteria could revolutionize waste disposal.

“The PET-digesting enzymes offer a way to truly recycle plastic,” notes Mark Lorch, a senior lecturer in biological chemistry at the University of Hull in England. “They could be added to vats of waste, breaking all the bottles or other plastic items down into easy-to-handle chemicals. These could then be used to make fresh plastics, producing a true recycling system.”

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (26)