Photo: Pixabay/life_is_beautiful

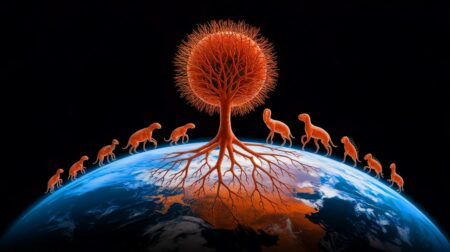

About 25 million kilometres of new roads are expected to be built around the world by 2050. Along with power lines and railways, roads cut through the landscape everywhere, disrupting ecosystems.

This linear infrastructure prevents animals from moving safely around their habitat. It also reduces access to the resources they need, like food, sufficient space and mating partners. This threat to biodiversity is a conservation issue globally, but especially in developing nations, where 90% of new road construction is expected.

The African continent is home to unique biodiversity and extraordinary landscapes. Planned infrastructure developments will certainly threaten some of the last, unspoilt wildernesses on the continent.

We’re particularly concerned about the future of primates. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists half of the continent’s 107 primate species as threatened.

According to the IUCN 18% of the world’s primates are directly affected by roads and railroads and 3% by utility and service infrastructure. These figures are based on limited research, though. The true impact is likely to be higher.

South Africa’s case shows why. None of the South African primate species currently have linear infrastructure listed as a threat under the IUCN. But this doesn’t mean they are not negatively affected. It just means that the lists need to be better informed.

South Africa is the only African country that has long-term, country-wide mortality datasets for both wildlife roadkill and wildlife electrocution. It’s collected by patrol staff, scientists and the general public (citizen scientists).

Using this data, we investigated how roads and power lines affect South Africa’s five primate species: the chacma baboon (Papio ursinus), the vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), the samango monkey (Cercopithecus mitis), the lesser bushbaby (Galago moholi) and the greater or thick tailed bushbaby (Otolemur crassicaudatus).

All species were affected, mostly by roads. We found a total of 483 deaths captured in the databases between 1996 and 2021. The number of deaths is likely to be a lot higher, due to under-reporting. Targeted species- and area-specific surveys are needed to refine this dataset.

The more mortality data is available, the better we will understand impacts, know where to focus interventions and inform future infrastructure developments to lessen the human impact on biodiversity.

We recommend that infrastructure like roads and power lines be more prominently recognised as a direct threat when developing Red List assessments.

Primate deaths

Most of the electrocution data used in our study was accessed from the Eskom Central Incident Register.

Roadkill data for our study was available from two sources: the national database from the Endangered Wildlife Trust’s Wildlife and Transport Programme and our own observations.

Since 2011, the Endangered Wildlife Trust has received records from systematic patrols on certain highways and species -and area-specific expert research surveys. Citizen science data comes from all over the country including national and regional roads, with differing speed limits, widths and vehicle usage.

The area surveyed by systematic patrols amounts to 1,370 km, covering 0.2% of the country’s entire road network and 0.9% of the paved road network.

The highest number of deaths recorded was for vervet monkeys. This was to be expected as vervet monkeys have a much wider geographic range in South Africa than both bushbaby species and the samango monkey, so they have a greater chance of encountering roads and power lines.

The greater (or thick tailed) bushbaby and the samango monkey are forest associated and forests cover only about 0.1% of South Africa’s land surface area.

Although the total of 483 primate deaths over 25 years may not appear very high, we can assume that many remain undetected. For example scavengers might remove the dead animals, or they could be hidden by dense vegetation on road verges. They could be in remote places, in the case of power lines, or severely injured animals might die later, a distance away from the road.

For roads, the actual mortality rate could be 12–16 times higher than the detection rate.

Solutions

Encouragingly, there is more and more research showing that primates, as well as many other tree-dwelling species, accept man-made canopy bridges as a means to cross gaps in their habitat.

In South Africa we conducted an experiment in the field to test what kind of canopy bridge primates would use to cross gaps between trees. We found that all five South African primate species used the canopy bridges offered to them. The design they preferred was a solid pole bridge, rather than a ladder bridge.

More and more canopy bridges of various kinds are being provided in different countries. But research shows that Africa is lagging behind other continents in doing this, and there are no canopy bridges in South Africa. We suggest that all infrastructure development projects should try to give attention to maintaining the integrity of landscapes, for example by providing bridges for animals.

We all need and use linear infrastructure in our day to day lives, so we all carry some level of responsibility. Hence, we encourage people to record wildlife mortalities and submit them to publicly available repositories such as iNaturalist or the Global Biodiversity Information Facility.

A new Global Primate Roadkill Database is also being developed by Laura Praill at Oxford Brookes University and colleagues and should be available to the public by April 2023.

Public awareness and participation is essential to lessen the human impact on biodiversity.

This article was written by , a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Venda, and , a research fellow abd South African Research Chair in Biodiversity Value & Change at the University of Venda. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (24)