Scientists in Belgium say that air pollution is affecting human health even before birth, and they’ve provided the first direct evidence that airborne carbon particles are crossing the placental barrier in pregnant women.

That’s according to research published by the Hasselt University scientists in the journal Nature Communication, where they discuss findings based on an intersection of expertise from the university’s biomedical research and environmental science centers.

“Particle transfer across the placenta has been suggested” but without prior evidence, said the research team led by Dr. Hannelore Bové and Dr. Tim Nawrot. “Our finding that black carbon particles accumulate on the fetal side of the placenta suggests that ambient particulates could be transported towards the fetus and represents a potential mechanism explaining the detrimental health effects of pollution from early life onwards.”

Their findings were based on results drawn from careful examination of 28 placentas, Bové said. The team used successful laser-light techniques that previously found soot particles in blood and urine samples.

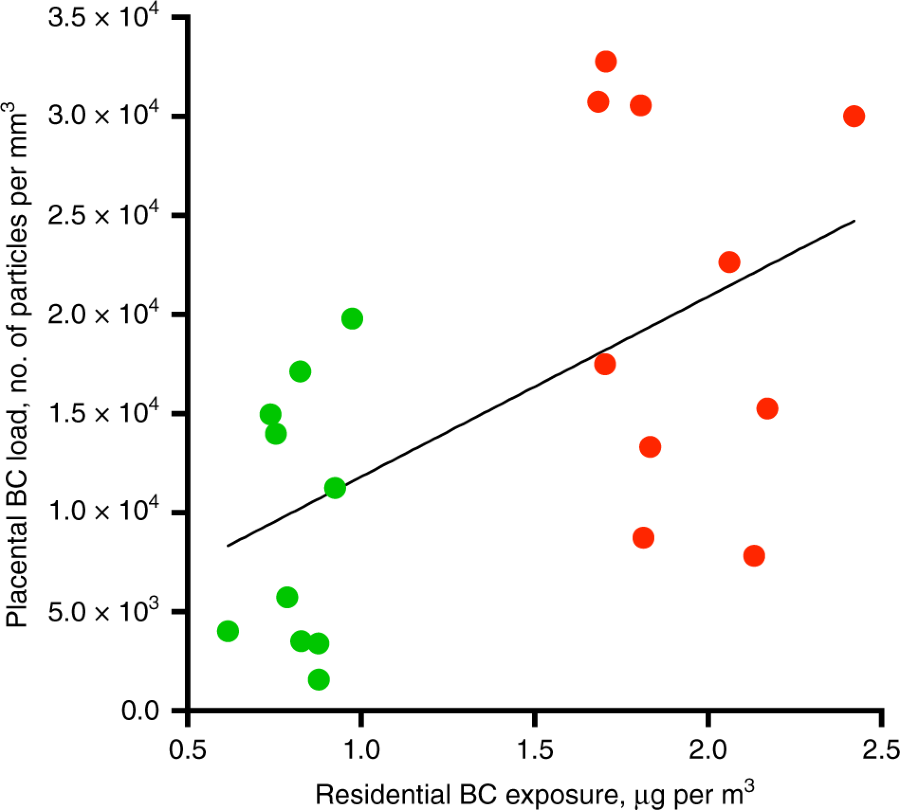

“We show that with this unique technique we can also detect soot particles in tissues such as placenta,” Bové added. The Hasselt team, looking at the 10 lowest and highest concentrations they found, also determined that where women lived – in other words, how close to roads or diesel exhaust or fossil-fuel industrial emissions – added to their risk of transferring soot across the placenta to the developing child.

The exposure also comes very early in the pregnancy, with soot detected at 12 weeks gestation, Bové said. That sets up concern over fetal development. “It is also striking that we found a higher concentration of soot particles on the fetal side of the placenta than on the mother’s side,” she added. “This means that soot particles are gradually accumulating on the fetus side.”

Nawrot added that we already know that air pollution is harmful, and that soot can be carcinogenic. “During pregnancies, air pollution is linked to premature births and a lower birth weight. With this research we want to find out more about how soot particles play a role during pregnancy,” he said.

The researchers say that exposure to soot pollution in the fetus must now be further investigated. They plan to continue looking at newborns, with plans to study the placentas of more than 1,000 babies through the Limburg Birth Cohort, a scientific-study collaboration between Hasselt and a regional hospital that began in 2010.

“In fifty years we will look back at these results and we will be shocked that so long, so little has been done in our society against soot pollution,” the researchers said. “Just as we now look back with surprise at the fact that smoking was still permitted everywhere a few decades ago.”

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (24)