Honey has long been touted as a natural alternative with medicinal properties, notably in wound care – and now there’s new evidence that it may offer healing benefits inside the body following surgery, when used in tandem with the medical meshes often layered against human tissue.

Researchers in the United Kingdom say the technique depends on Manuka honey, a type that comes from bees feeding on the manuka bushes of Australia and New Zealand. Its value has long been known: A 1991 study found Manuka honey maintains its ability to kill bacteria because it contains methylglyoxal, an ingredient that makes its antimicrobial powers different from other honey types.

Yet the breakthrough published in the journal Frontiers relies on cutting-edge nanotechnology that sandwiches the ancient remedy in minute layers within the surgical meshes. Existing meshes help people to heal – they’re commonly used following hernia surgeries – but at the same time, they usually increase the patients’ risk of infection because bacteria that enters the body clusters into a film on the meshes.

Finding ways to make surgical mesh so it doesn’t carry a high risk for recovering patients is the goal.

The success, reported by Dr. Piergiorgio Gentile of Newcastle University and Dr. Elena Mancuso of Ulster University, is important because when infections occur they are usually treated with antibiotics.

“Skin and soft tissue infections are the most common bacterial infections, accounting for around 10 percent of hospital admissions, and a significant proportion of these are secondary infections following surgery,” the authors explain. “The emergence of antibiotic resistant strains – or ‘superbugs’ – means scientists are on the hunt for alternatives.”

Combating the rise of these antibiotic-resistance strains is a World Health Organization priority, and more than one study suggests a possible link to climate change. A European study presented earlier this year looked at 30 different countries and found enough evidence to consider an intersection between climate factors and the growing threat of antibiotic resistance now, while raising questions about how a hotter, wetter world might complicate antimicrobial resistance in the future.

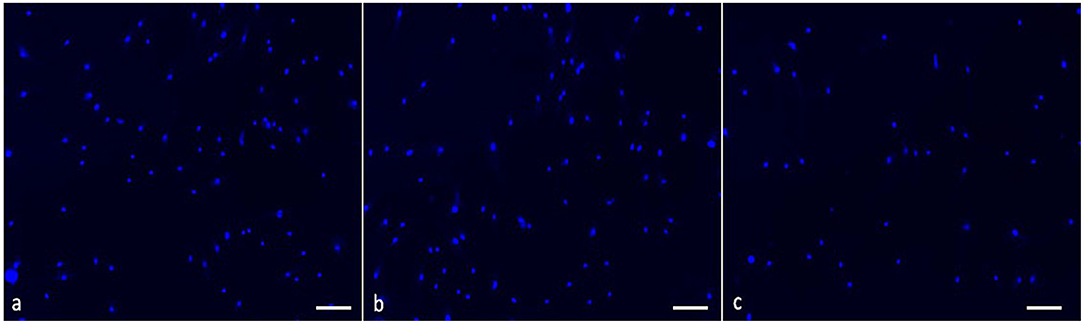

So the work from Gentile and Mancuso isn’t a curiosity, so much as it addresses an existing problem that global health experts worry will grow worse. The surgical meshes they developed, with eight layers of negatively charged Manuka honey and eight layers of positively charged polymers, can maintain the protective properties against bacterial infection for up to three weeks, based on the lab performance.

“Too little honey and it won’t be enough to fight the infection but too much honey can kill the cells,” Gentile said. “By creating this 16-layered ‘charged sandwich’ we were able to make sure the honey was released in a controlled way over two to three weeks which should give the wound time to heal free of infection.”

Mancuso and Gentile say they’re excited about the results. “Honey has been used to treat infected wounds for thousands of years but this is the first time it has been shown to be effective at fighting infection in cells from inside the body,” Gentile added.

That’s one more reason to appreciate honey – and to protect the bees that are producing it.

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (23)