On New Year’s Eve of 2020, the carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere measured 415 parts per million at the Mauna Loa monitoring site operated by NOAA in the United States.

On New Year’s Day of 2021, the CO2 reading was 447 ppm at the same site – so long as it was being read from the pages of “The Ministry for the Future,” the latest novel from science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson. That CO2 reading from the book, whose characters arrive in the near-future year of 2025, rises to 475 ppm as the story unfolds before the CO2 level ultimately begins its slow descent.

“It was down to 451 now, same as in the year 2032, and it was on a clear path to drop further, maybe even all the way to 350,” writes Robinson in Chapter 94, the same chapter that mentions the 58th COP meeting of the Paris Agreement signatories. (In reality, the postponed 2020 meeting in Scotland is the 26th such COP meeting.)

“The discussion now was how far down they wanted to take it,” Robinson continues. “This was a very different kind of discussion than the one that had commanded the world’s attention for the previous forty years.”

The book itself has been at the center of much discussion, but it would be a mistake to assume that Robinson’s work is an optimistic adventure, a tale of humanity’s success in pulling the planet back from the brink of catastrophe. The story begins with the deaths of 20 million people in India after a cruel and unprecedented heat wave.

There are countless more deaths to follow, some at the hands of ecoterrorists forcing an end to air travel or meat consumption, some as assassinations of those implicated in carbon-intensive industries or those whose policies failed to curb them. Even the Ministry for the Future itself, established as a United Nations agency to advocate on behalf of future generations and led by main character Mary Murphy, has a shadowy hand in such operations and becomes the target of a bombing at the headquarters in Zurich.

It’s true that Robinson’s people make uneven progress – often through geoengineering strategies – when it comes to reducing India’s heat or controlling Antarctic ice melt. His treatment explores the technical aspects of the climate fight, to be sure, but he weaves the political and the financial, the historical and the linguistic, the scientific and the sentimental into a cord of inseparable strands that bind his characters and the inhabitants of Earth to each other.

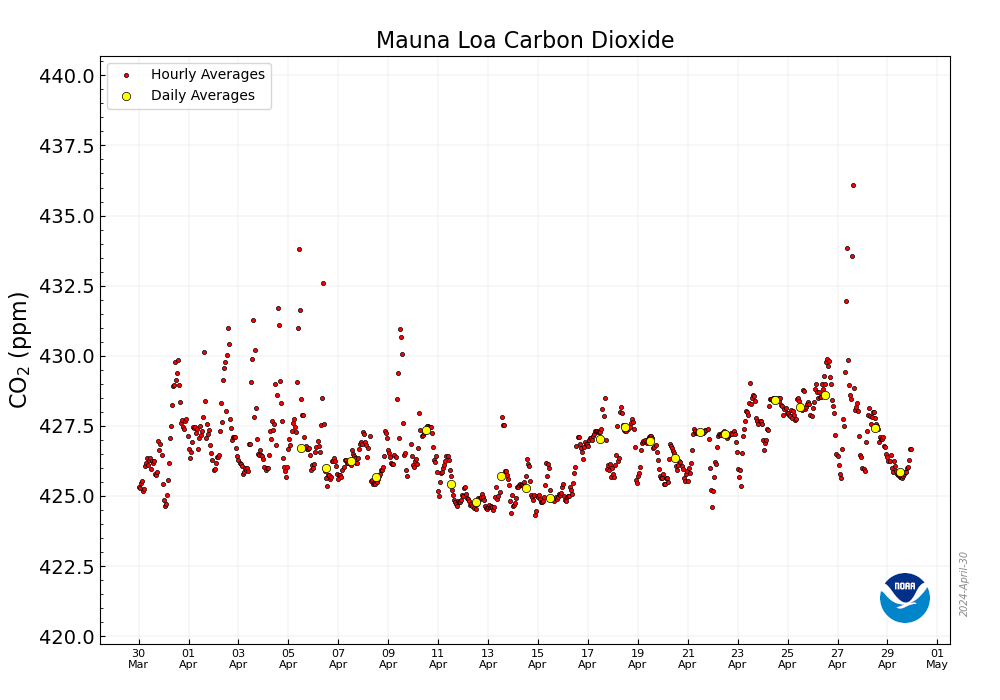

Like the CO2 readings at Mauna Loa, creeping up in the nonfictive present, what’s clear at the start of this new year is that the ministry’s future is now even if the future generations are not. “It’s not science fiction,” notes climate champion Bill McKibben in his review of the book.

Robinson’s richly detailed work is really an amplification of the present, one vision of how this present might evolve in the coming decades. The climate organizations and movements he refers to, the cutting-edge technologies in shipping or agriculture or blockchain currency or drone applications, should be familiar to those who closely follow climate news and innovation.

There’s hope, and Robinson tells one interviewer that he considers hope a moral obligation. Yet – and all the more so as a new year begins – that hope is tempered by the knowledge that climate impacts are unavoidable, so are changes to human experience, and there is no more time to delay action.

“The situation we’re in is radically dangerous,” Robinson told Amy Brady at the Chicago Review of Books. “We’re entering a decade of intense conflicts all across the board. In a situation like that you end up saying things like, ‘Wow, I hope civilization survives.’ That’s still hope, right?

“And beyond that, it’s worth saying, if we succeed in inventing and installing a global post-capitalist world order focused on justice and long-term sustainability, results could be really good, really exciting. I think that’s still true, so despite the conflicted years we’re entering now, that thought gives me hope.”

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (26)