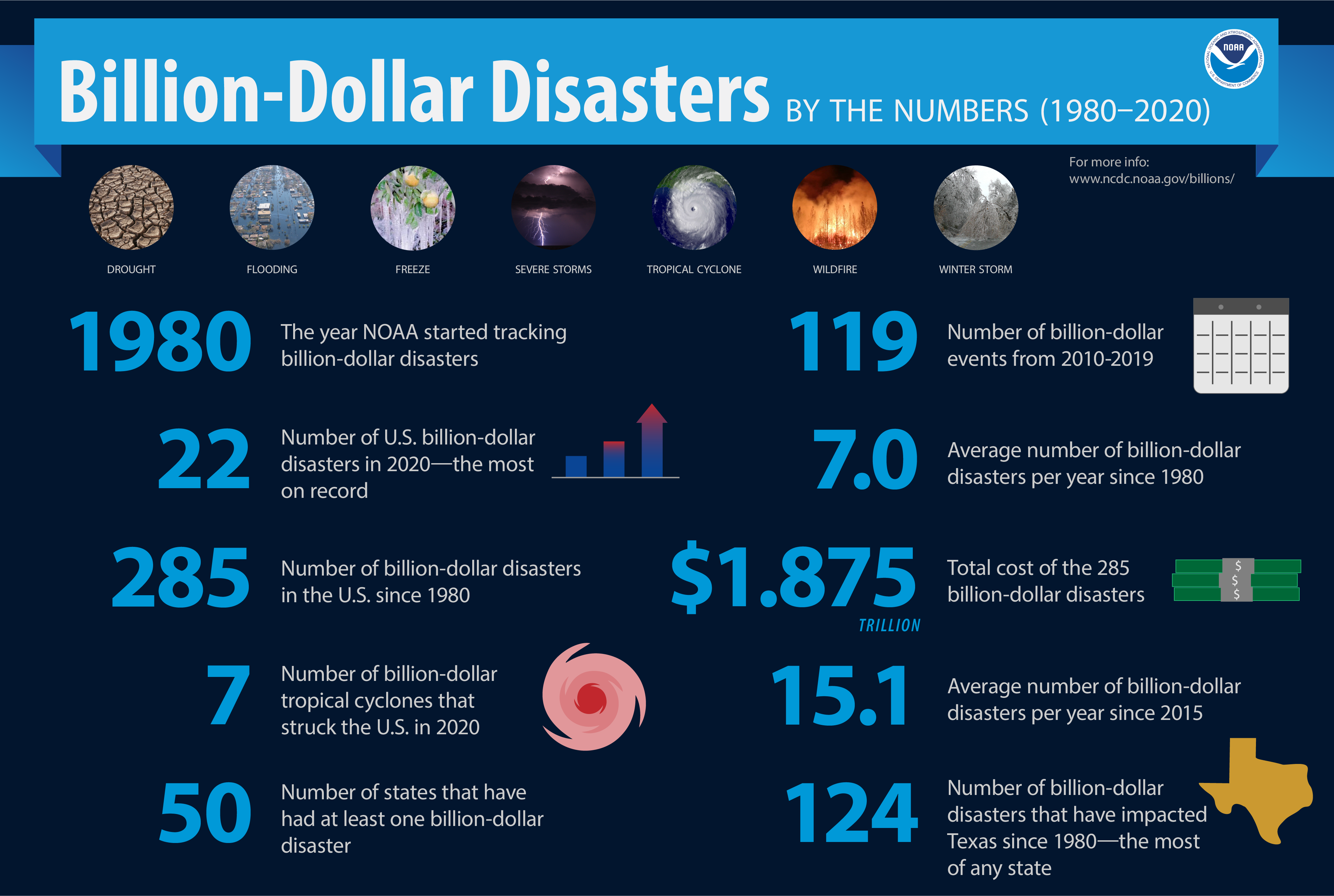

The United States saw more than $95 billion in disaster-related damages in 2020, arising from 22 separate billion-dollar weather and climate catastrophes, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“It was a historic year of extremes,” says Adam Smith, the lead scientist for the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information’s program to evaluate these costly disasters. “Most strikingly, this included the record-breaking Atlantic hurricane and Western wildfire seasons. Many central states also endured a severe derecho of historic intensity that produced impacts similar to an inland hurricane.”

The NOAA program has evaluated billion-dollar disasters since 1980, and this year saw the most incidents to reach the impact threshold. Among the worst events was Hurricane Laura, with its storm surge and 240 kilometer per hour winds that devastated the Louisiana Gulf Coast when the storm made landfall on August 27.

Laura was one of a record-setting 30 tropical storms for the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, with 12 of them making landfall in the United States and seven of them exceeding the $1 billion threshold.

But coastal regions weren’t the only ones lashed by storms. A derecho is a windstorm that continues for at least 400 kilometers with winds of at least 93 km/h, and the August storm that began in Nebraska caused widespread damage across at least five U.S. states. All told, the damages tallied up to $11 billion.

Smith says the tropical storms are what usually cause the most devastation, but incidents like the derecho and the aggressive wildfires also wreak havoc. Last year was the sixth consecutive year that the U.S. saw 10 or more billion-dollar disasters, and the experts say climate change definitely has played a role.

It’s not the only factor, because where and how humans build homes and communities – and how those properties are valued – are part of the calculation.

“These trends are further complicated by the fact that much of the growth has taken place in vulnerable areas like coasts and river floodplains. Vulnerability is especially high where building codes are insufficient for reducing damage from extreme events,” said Smith.

“Climate change is also playing a role in the increasing frequency of some types of extreme weather that lead to billion-dollar disasters—most notably the rise in vulnerability to drought, lengthening wildfire seasons in the Western states, and the potential for extremely heavy rainfall becoming more common in the Eastern U.S.”

California lost about 4 percent of its land to wildfires in what became the state’s worst wildfire season on record, with five of the six largest wildfires in its history occurring in 2020. The western mountain state of Colorado also saw the three largest wildfires in its history last year.

Smith says the scale and complexity of a disaster sometimes make it harder to assess the impacts. The hurricanes, for example, might impact businesses but also boats, homes and crops, and it takes time to understand wind rather than water impacts and calculate the losses.

“These loss assessments do not take into account losses to natural capital, physical or mental healthcare-related losses, or indirect costs such as losses within economic supply chains,” he adds. “Therefore, our estimates should be considered conservative with respect to what is truly lost, but cannot be completely measured.”

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (29)