Cambodia’s last wild tiger is dead and he died in captivity. Jasper, as the 21-year-old tiger was called, was rescued as a cub from poachers, who helped drive Indochinese tigers extinct in the Southeast Asian nation within just a few short years.

After being taken from the wild for his own safety in 1998, Jasper spent almost his entire life protected under armed guard in the Phnom Tamao Wildlife Rescue Centre. According to the Wildlife Alliance, a nonprofit that runs the center for rescued animals, Jasper is “believed to be the last remaining Indochinese tiger from Cambodia’s forests.” He died of natural causes in old age.

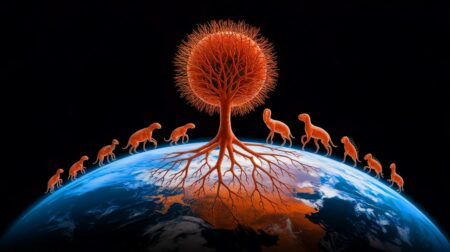

And so another chapter in the storied life of these magnificent animals has come to an end. And unless conservation efforts are stepped up for the last few hundred tigers in Southeast Asia, where two subspecies have already been driven extinct in living memory (in Bali and Java), the striped predators may well be doomed in the wild everywhere across the region.

Just two decades ago Cambodia still had one of the world’s highest tiger populations, according to some estimates. Yet within a decade almost all the big cats in the war-torn country lost out to habitat loss and poachers.

By 2007 only a single Indochinese tiger was known to be roaming local forests when the animal was last seen on camera traps placed in Cambodia’s forests.

No one has seen a wild tiger in the country since. Cambodia is planning to reintroduce tigers into the wild, but how well that project will go remains to be seen. The fear is that no longer will tigers be returned to local forests than poachers will kill them for their body parts, which are highly valuable on the black market because they are used as ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine.

Nor is it only in Cambodia where tigers are on their last legs. Outside of India, where the local Bengali tiger population remains relatively robust, the numbers of the big cats have plummeted to dangerous lows.

The watchdog Conservation Assured Tiger Standards (CA|TS), which monitors tiger reserves around Asia, recently surveyed 112 tiger conservation areas in 11 countries around Southeast Asia and farther afield. It found that only 13% of them meet global standards. A third of these conservation areas are at risk of losing their tigers because of inadequate protection and poor management.

In the survey the group’s researchers evaluated management practices at these sites that cover more than 200,000 square kilometers in all and account for some 70% of the world’s remaining wild tiger population. The countries surveyed included Thailand, Myanmar, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Nepal, India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, China and Russia.

“[B]asic needs such as enforcement against poaching, engaging local communities and managing conflict between people and wildlife, remain weak for all areas surveyed,” the researchers note. Somewhat more encouragingly, they add that at two-thirds of the sites management practices were found to be “fair to strong,” which gives us some hope that resident tiger populations could be saved in coming years from further harm.

The gravest threat facing wild tigers, in addition to habitat loss, has been rampant poaching.

“From whisker to tail, every inch of a tiger is valuable to poachers and traded in illegal wildlife markets,” said Ginette Hemley, senior vice president for wildlife conservation at the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF).

“The fight to save tigers has united governments and conservation organizations, but wild tigers won’t rebound until there are enough boots on the ground protecting them,” Hemley added.

Yet despite the ever-present danger of poaching staff at most reserves are ill equipped to protect local tigers. At 85% of the areas surveyed staff do not have the wherewithal to go on patrols often enough, while at 61% of the areas in Southeast Asia there is only very limited anti-poaching enforcement in place, according to the researchers.

Much of this has to do with a lack of funding, especially in Southeast Asia where only 35% of areas have robust enough finances, as opposed to 86% of sites in South Asia, Russia and China.

“Unless governments commit to sustained investments in the protection of these sites, tiger populations may face the catastrophic decline that they have suffered over the last few decades,” said Michael Baltzer, chair of the Executive Committee of CA|TS. “This funding is needed urgently, particularly for many sites in Southeast Asia to support recovery of its tiger population.”

Time is running out for wild tigers. A century ago some 100,000 tigers roamed far and wide across Asia. Today a mere 4,000 or so of the big cats remain, almost all of them beleaguered throughout their range from Malaysia to Russia. The situation is dire in every tiger-range country except India, which is home to around 2,500 wild tigers that account for more than half of the world’s wild tiger population.

Next comes Russia with more than 400 tigers, followed by Indonesia with almost as many, then Malaysia and Nepal with around 200 each. Even the loss of a few dozen more tigers in many of these countries could have catastrophic consequences for local tiger populations.

In order to boost wild tiger populations everywhere, or at least stop them from falling further, conservation efforts need to be strengthen. Governments have a vital role to play in that.

“Ineffective management of tiger conservation areas leads to tiger extinction,” warns S.P. Yadav, an expert at the international conservationist outfit Global Tiger Forum. “To halt and reverse the decline of wild tigers, effective management is thus the single most important action.”

Yadav adds: “To achieve this, long-term investment in tiger conservation areas is absolutely essential, and this is a responsibility that must be led by tiger range governments.”

Did you like it? 4.4/5 (28)