The ever-increasing melt of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is now unavoidable, according to British Antarctic Survey (BAS) research published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change. But while lead author Dr. Kaitlin Naughten is clear that “even the best-case scenario was still very bad,” she doesn’t want people to despair at the news.

“I would hate for people to read this story and think ‘we should give up on climate action, we’re all doomed anyway,'” said Naughten in Monday’s social media discussion of her work. “We must remember that West Antarctica is just one cause of sea level rise, and sea level rise is just one impact of climate change.”

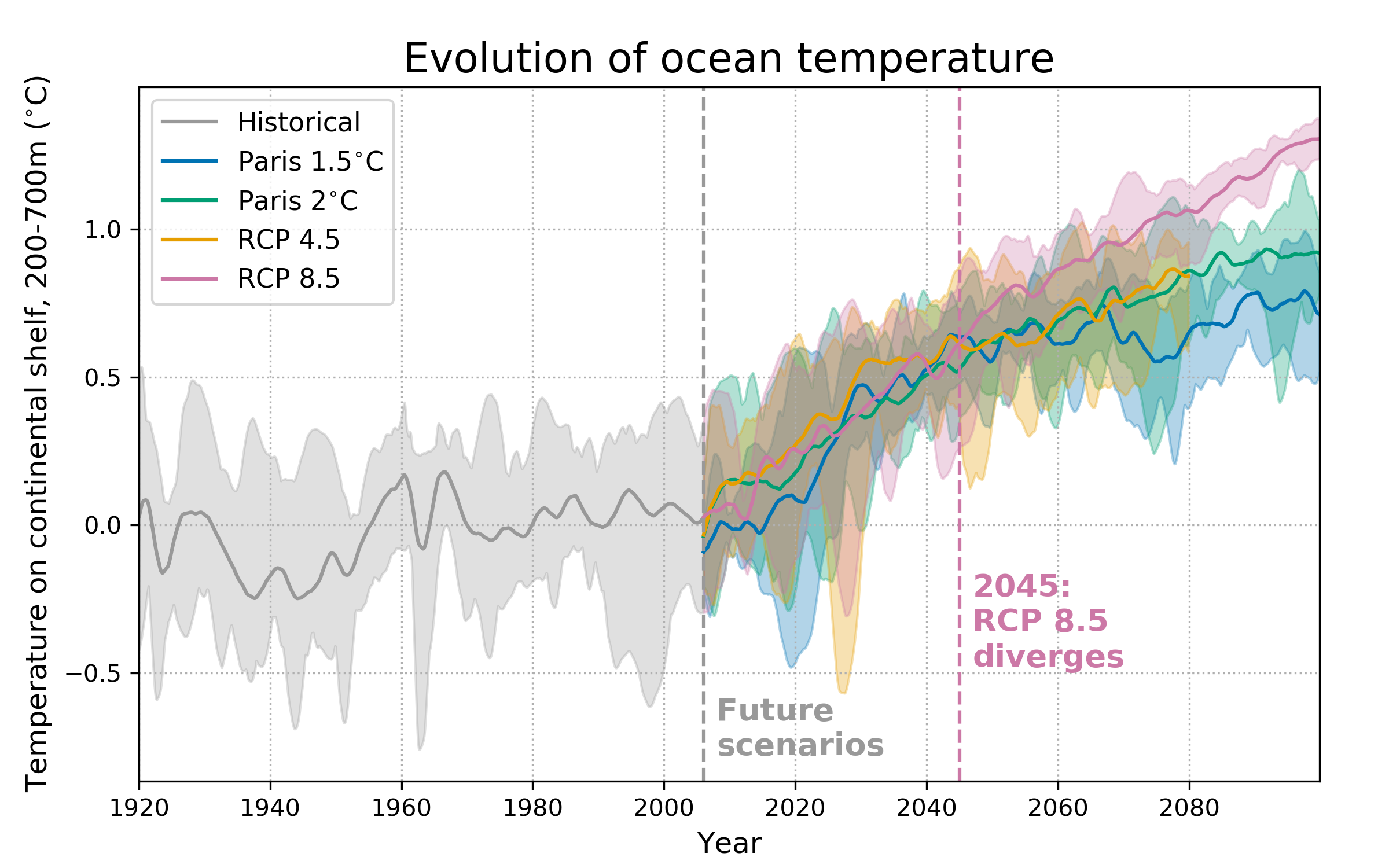

Still, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is Antarctica’s largest contributor to sea-level rise. It amounts to enough ice that could, when melted, raise global mean sea level by up to five meters. When Naughten and her team ran models based on various projections of climate warming, they found little to no difference between the 1.5°C impacts (now considered optimistic) and the 4.5°C impacts of business-as-usual.

Either way, the ice melts and causes sea-level threats for coastal communities around the world, including the most vulnerable island nations and low-lying countries like Bangladesh. The melt could rapidly increase in the coming decades, at a rate three times faster than during the 20th century. Even under the best-case scenario, the floating ice shelves melted though the rate starts to flatten by 2100. The unlikely worst case meant more ice shelf melting than any other scenario, but only after 2045.

Previous studies have demonstrated how greenhouse gas emissions are linked to the melting. For example, Southern Hemisphere westerly winds are affected by emissions. The winds force warm water currents under and around the ice, contributing to its warming.

Naughten says that she and co-authors Paul Holland and Jan De Rydt have now been able to deliver the most comprehensive set of future projections on the Amundsen Sea ice shelf melting. The numbers make clear that fossil fuel use must be reduced, and that decisions made now will help to slow the rate of sea level rise and allow people and governments to adapt to conditions that can no longer be stopped.

Adaptation should now be considered more seriously as a priority in the world’s response to sea-level rise, along with mitigation. Luck will help, too, the authors note.

“It looks like we’ve lost control of melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. If we wanted to preserve it in its historical state, we would have needed action on climate change decades ago,” said Naughten.

“The bright side is that by recognizing this situation in advance, the world will have more time to adapt to the sea level rise that’s coming,” she added. “If you need to abandon or substantially re-engineer a coastal region, having 50 years lead time is going to make all the difference.”

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (25)