Amid mounting case counts of the monkeypox virus, reported from countries with little to no history of exposure, are questions about whether and how monkeypox is related to climate change. The answer is complicated, but global health officials say there is a clear link between the two.

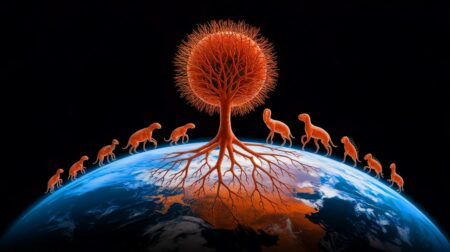

Much of that has to do with the shrinking space between human communities and wildlife habitats. Dr. Mike Ryan, the World Health Organization’s executive director for health emergencies, says that as the planet deals with rising levels of ecological fragility and climate stress, it’s changing both animal and human behavior.

“It’s changing the range of animals. It’s changing food-seeking behavior and many other things,” said Ryan, during a recent WHO discussion on global health.

“We’re dealing with the animal-human interface being quite unstable and the number of times that these diseases cross into humans (is) increasing,” Ryan added. “Then, our ability or, unfortunately, that ability to amplify that disease and move it on within our communities increasing.”

As of June 4, WHO reported 780 confirmed monkeypox cases in 27 countries that are not known to be endemic for the virus. It’s typically seen in Western and Central Africa, where the virus was first identified more than 50 years ago.

There have been occasional travel-related cases outside of the African continent in the past, but now the virus is spreading within communities in other countries, notably with more than 200 cases in the United Kingdom. Spain and Portugal account for nearly 300 cases. Germany has seen 57 and France reports 33 cases. There are now 31 cases across the United States as well, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports.

“Most confirmed cases with travel history reported travel to countries in Europe and North America, rather than West or Central Africa,” the WHO said. “Confirmation of monkeypox in persons who have not traveled to an endemic area is atypical, and even one case of monkeypox in a non-endemic country is considered an outbreak.”

Human behavior is behind the spread of the disease but that doesn’t explain its origins. The CDC says the precise animal reservoir, or source, of monkeypox infections remains unclear but it is associated with rodents and non-human primates, like monkeys.

And in a world of climate-driven drought, habitat loss and other stresses, it’s more likely for infections to cross from animals into humans.

“Both disease emergence and disease amplification factors have increased and therefore it’s not just in monkeypox. It is in other diseases,” says Ryan. “These are generally diseases of small mammals. We’ve seen similar with aviation influenza and again that strain at that animal-human interface between us and birds, effectively.”

There’s an upward trend in Lassa fever, in Ebola outbreaks too. “We used to have three-five years between Ebola outbreaks at least. Now, it’s lucky if we have three-five months,” Ryan said.

It’s relatively rare for monkeypox to be fatal, and WHO is not yet recommending mass vaccinations (there is a vaccine, although the smallpox vaccine is more likely available). WHO and its partners are focusing on monkeypox research, and recommitting their support for African nations where monkeypox is an ongoing reality, as well as in the newly affected regions.

But climate factors need to be addressed too, Ryan said.

“I think what we’re generally seeing here is this hyperendemicity, as in endemic diseases at small levels becoming more persistent, more frequent and generating more and more outbreaks,” Ryan said. “I think that that’s a lesson, not just for monkeypox. It comes back to our lack of investment in that animal/human interface, particularly in countries that don’t have the systems in place to do the diagnosis and do the interventions.”

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (29)