There is no perfect energy source. Conservation professionals and environmental advocates need to take an evidence-based approach.

A nuclear option for saving wildlife habitats?

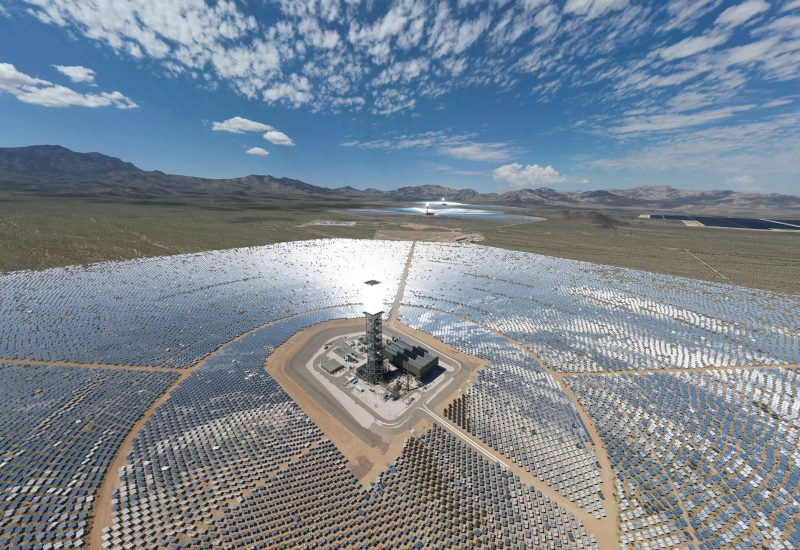

No form of energy generation is without at least some environmental costs, and those costs include threats to beleaguered wildlife worldwide. Take renewables. Hydropower dams may be emissions-free but they can wreak havoc on aquatic species by irreversibly changing local water conditions. Solar and wind farms, meanwhile, require plenty of space, which, too, can come at the expense of biodiversity by further reducing already diminished wildlife habitats, especially in areas where available land is sparse enough as it is.

This has not escaped the attention of some conservationists. As Barry W. Brook, professor of Environmental Sustainability at the University of Tasmania, and Corey Bradshaw, professor of Ecological Modelling at the University of Adelaide, wrote in 2014: “Ultimately, there is no perfect energy source. Conservation professionals and environmental advocates need to take an evidence-based approach to consider carefully the combined effects of energy mixes on biodiversity conservation.”

That evidence-based approach indicates that nuclear power should play a far larger role in future energy packages, according to the two conservation experts. “When compared objectively with alternatives, nuclear power performs as well [as] or better than other options in terms of safety, cost, scaleability, reliability, land transformation and emissions. And overall, the mix including a substantial role for nuclear performed better than the other scenarios,” explain Brook and Bradshaw, who coauthored a study on the role of nuclear energy in wildlife conservation.

“Although our analysis was based on existing nuclear designs, we were most excited about the advantages offered by next-generation nuclear power now under construction in Russia and China,” they elucidate. “If deployed widely, this technology could provide emissions-free electricity, by recycling a highly-concentrated energy source in a way that consumes waste and minimises impacts to biodiversity compared to other energy sources.”

Brook and Bradshaw were among 75 conservationists, biologists and wildlife experts who signed a letter calling on their fellow environmentalists to embrace nuclear power. “Although renewable energy sources like wind and solar will likely make increasing contributions to future energy production, these technology options face real-world problems of scalability, cost, material and land use, meaning that it is too risky to rely on them as the only alternatives to fossil fuels,” the scientists explained in their open letter. “Nuclear power — being by far the most compact and energy-dense of sources — could also make a major, and perhaps leading, contribution.”

Nuclear energy, its proponents among conservationists stress, has a low environmental impact. It does not release greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide or methane beyond those emitted during the extraction and transportation of uranium through fossil fuel use. Nor does a modern nuclear power plant have much of an adverse effect on local water sources, land use or wildlife habitats (although cooling water discharged from plant can interfere with some aquatic species by altering ambient water temperatures, while pollutants and toxins may be released during the mining of uranium). Just as importantly, nuclear energy provides abundant electricity in an efficient and reliable manner, regardless of weather conditions.

Yet nuclear power is still not widely popular among conservationists. One reason is that the actual environmental risks posed by plants tend to be misunderstood. “Radiation and safety [issues] are nothing to worry about and any way you cut it, [nuclear] is the best of all energy sources,” insists Agneta Rising, director general of the World Nuclear Association. “But of course it is perceived differently, and therefore we must contribute to the efforts to mitigate climate change and to give people ample electricity and raise their quality of life.”

What is needed, nuclear experts argue, is a sea change in public perception about the benefit of nuclear power. Without more nuclear in future energy packages, they say, reductions in global emission targets are highly unlikely to be met in coming decades, which will compromise efforts to mitigate the effects of climate change. “Green people support a lot of renewables [but] maybe they do not know [enough] about nuclear alternatives for the future,” argues Mikhail Chudakov, deputy director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“The important factor is public acceptance. We need to explain [the benefits of nuclear power] from teaching it in schools to having conferences to meeting with government officials and presidents,” Chudakov adds. “We need to gain public acceptance, and we should do this together with international organizations, and not be ashamed of talking about nuclear… We should start now to change the minds of billions of people. We need to change the paradigm about nuclear energy.”

Changing that paradigm entails emphasizing the need for nuclear power in the face of ever-increasing energy needs worldwide, Rising agrees. “Nuclear energy is essential, and many of the documents and reports show that if we are to have sustainable energy in the future we are going to need a large proportion of nuclear energy, and we do not have that,” she explains. “[Our] electricity consumption is so great that we need something that is dispatchable and available 24/7, irrespective of weather.”

Another benefit is sheer efficiency. A small amount of uranium can fuel a reactor for decades during the lifespan of a plant that can last for as long as 60 years. A mere 28 gram of uranium releases as much energy as 100 metric tons of coal, which can make a world of difference to the environment.

“To avoid a business‐as‐usual dependence on coal, oil, and gas over the coming decades, society must map out a future energy mix that incorporates alternative sources,” Brook and Bradshaw emphasize. “This exercise can lead to radically different opinions on what a sustainable energy portfolio might entail, so an objective assessment of the relative costs and benefits of different energy sources is required,” they add.

In their study, the two conservationists ranked seven major electricity‐generation sources (coal, gas, nuclear, biomass, hydro, wind, and solar) based on their relative costs and benefits. What they found was that nuclear and wind energy had the highest benefit‐to‐cost ratio. Yet in order to generate enough electricity to power modern economies by themselves, wind farms would need to be set up on vast tracts of land and sea. For want of alternatives, those large swathes of land might have to be taken not only from agricultural farmland but from remaining wildlife habitats as well.

“Although the environmental movement has historically rejected the nuclear energy option, new‐generation reactor technologies that fully recycle waste and incorporate passive safety systems might resolve their concerns and ought to be more widely understood,” Brook and Bradshaw point out. “Trade‐offs and compromises are inevitable and require advocating energy mixes that minimize net environmental damage. Society cannot afford to risk wholesale failure to address energy‐related biodiversity impacts because of preconceived notions and ideals.”

Ideally, the IEA says, nuclear power should account for at least 25% of global electricity generation by 2050. Encouragingly, some of the planet’s worst polluters, such as China and India, are taking notice of environmental costs and embracing nuclear energy.

They are among the 16 nations involved in the United Nations’ Deep Decarbonization Pathway Project with the aim of finding solutions to their energy conundrums through adopting cleaner and greener power sources. “Out of these 16 countries, not all use nuclear but they are discussing technologies, social factors, communities in their country, and where they will end up by 2050,” Rising notes. “These 16 countries could contribute to lowering 75% of the emissions in the world, but [to do so] they would need 1,000 gigawatts of nuclear capacity,” the expert says.

“I think countries like Bangladesh, Belarus, Turkey, and the UAE will be building reactors,” she adds. “They are [planning on] growing their economies and at the same time keeping their emissions low.”