A staggering 1.3 billion tons. That’s how much food we waste around the planet each year, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. All that food could feed millions upon millions of people in places like sub-Saharan Africa that face regular food shortages for environmental reasons.

And things are going to get worse before they get any better. With climate change upsetting traditional weather patterns across much of the planet, crop failures and food shortages will become increasingly likely in parts of the world, especially those with already low levels of food security. That could lead to famines of biblical proportions, the mass migrations of people and outbreaks of violence, which could destabilize entire regions, experts warn.

“There’s a one-in-20 chance that a major weather event could… wipe out the production of essentially 75 per cent of the world’s maize, overnight,” says Alison Martin, a risk officer at Zurich Insurance in Switzerland. “It would be like the African famines on steroids, on a scale we’ve never seen, basically. But if people don’t see these things happening, it’s out of sight, out of mind, while the terrible events that we do see happening are front of mind.”

Take coffee, a fruit beloved by millions around the planet. Some 2.25 billion cups of coffee are sipped and gobbled down daily worldwide. According to a recent report, appropriately titled “A Brewing Storm” and compiled by the Climate Institute, coffee crops worldwide are set to plunge in the face of warming temperatures. Coffee production could plummet by a staggering 50% in coming decades.

That would of course mean a significant rise in the price of coffee, which currently underpins a US$19 billion industry. “[B]y 2050, we might see as much as a 50 per cent decline in productivity and production of coffee around the world, which is not so good,” said Molly Harriss Olson, the chief executive of Fairtrade Australia and New Zealand, which commissioned the report.

Rising temperatures may harm heat-sensitive plants, including the hugely popular Coffea Arabica plant. It is cultivated widely in the famous “Bean Belt,” which girds the tropics and encompasses Brazil, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, among other countries. Arabica grows well at around 23 degrees Celsius but suffers at higher temperatures.

And local temperatures at several places where it is cultivated have already shot by up to 1.3 degrees Celsius. Tanzania, where coffee production is a major part of the local economy, has seen coffee yields almost halve already over the past half century. Coffee crops, which are routinely cultivated on hillsides, are also at increasing risk of succumbing to new diseases like coffee rust and to pests like a beetle called the coffee berry borer.

And it isn’t just changing weather patterns that are posing a threat to staple crops, including our favorite fruits. Bananas are cultivated wholesale in 120 countries across the tropics from South America to Africa to Southeast Asia. Collectively, these countries produce 100 million tons of the fruits each year.

Yet banana trees are at risk across the planet because of their vulnerability to diseases. According to a recent study by researchers in the US and the Netherlands, several strains of a fungus are posing grave threats to the world’s banana plants. In fact, the fungi could wipe out the planet’s entire crop of the essential fruits within a matter of years.

“Two of the three most serious banana fungal diseases have become more virulent by increasing their ability to manipulate the banana’s metabolic pathways and make use of its nutrients,” said plant pathologist Ioannis Stergiopoulos, who spearheaded the scholarly endeavor to sequence the genomes of the three Sigatoka fungi strains: yellow Sigatoka (Pseudocercospora musae), eumusae leaf spot (Pseudocercospora eumusae), and black Sigatoka (Pseudocercospora figiensis).

The three strains could prove fatal to banana trees by compromising their immune systems and undermining their metabolism by feeding on host plants’ sugars and other carbohydrates. Worse: the fungi could spread with alarming speed around the globe. In the 1950s, a deadly strain of the Panama disease, a soil-borne fungus that attacks plants’ vascular systems through their roots, did just that, wiping out almost all of the popular Gros Michel (“Big Mike”) bananas in Central and South America.

As Gros Michel bananas went nearly extinct, cultivators switched to Cavendish bananas, which were resistant to the disease-causing fungus and have since become ubiquitous in supermarkets worldwide. But then in the 1990s a new strain of the fungus, which originated in Taiwan, began to spread worldwide. Cavendish bananas have been under threat ever since.

The destructive Sigatoka pathogens, which were discovered in the previous century and whose genomes have now been sequenced, could similarly inflict immense damage on the world’s banana plants. In fact, they could eradicate all bananas within a decade, researchers say. A third of banana production already involves the application of fungicides, but many farmers cut costs by using sub-standard fungicides, which could aid the pathogens’s spread.

To make matters worse, bananas are grown from shoot cuttings and all the Cavendish bananas have been grown from a single plant, which means they are genetically identical clones of one another. With their limited genetic diversity, they are all the more susceptible to devastating diseases. A disease that can kill one plant can kill them all with equal ease.

The solution is simple: develop a new cultivar, or else genetically modify existing Cavendish plants to make them resistant to the fungal diseases. That, though, is easier said than done, especially when it comes to applying either solution on a global scale.

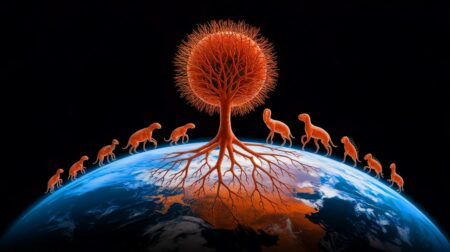

Bananas are large monocotyledenous herbs that originated in Southeast Asia with virtually all of the known cultivars having been handpicked from naturally occurring local hybrids by prehistoric farmers in countries like Thailand. Bananas were among the first plants cultivated by humans, yet ironically they may be the first plants, too, that may end up being lost to us.

We can’t just blame fungi for that, however. Fungi are amoral organisms that do what is in their best interest: thrive and spread any way they can. They destroy banana plants not because they are “evil” but because evolution has primed them to survive by destroying bananas and other plants susceptible to them.

But how about us? Why is it that Cavendish bananas, those tasty yet highly disease-prone fruits, have become so common worldwide? The answer lies in our insistence on having nothing but the best in our fruits and vegetables, including bananas. Driven by the spoiled ethos of our consumerist culture, we want bananas to taste just so and we want them to look just so, too (nice and large and without any spots or blemishes).

Banana producers have been happy to oblige, in their search of hefty profits, by investing all their resources in a single crop. And so there you have it: in our quest for perfect bananas, we may have unwittingly sown the seeds of their destruction.

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (24)