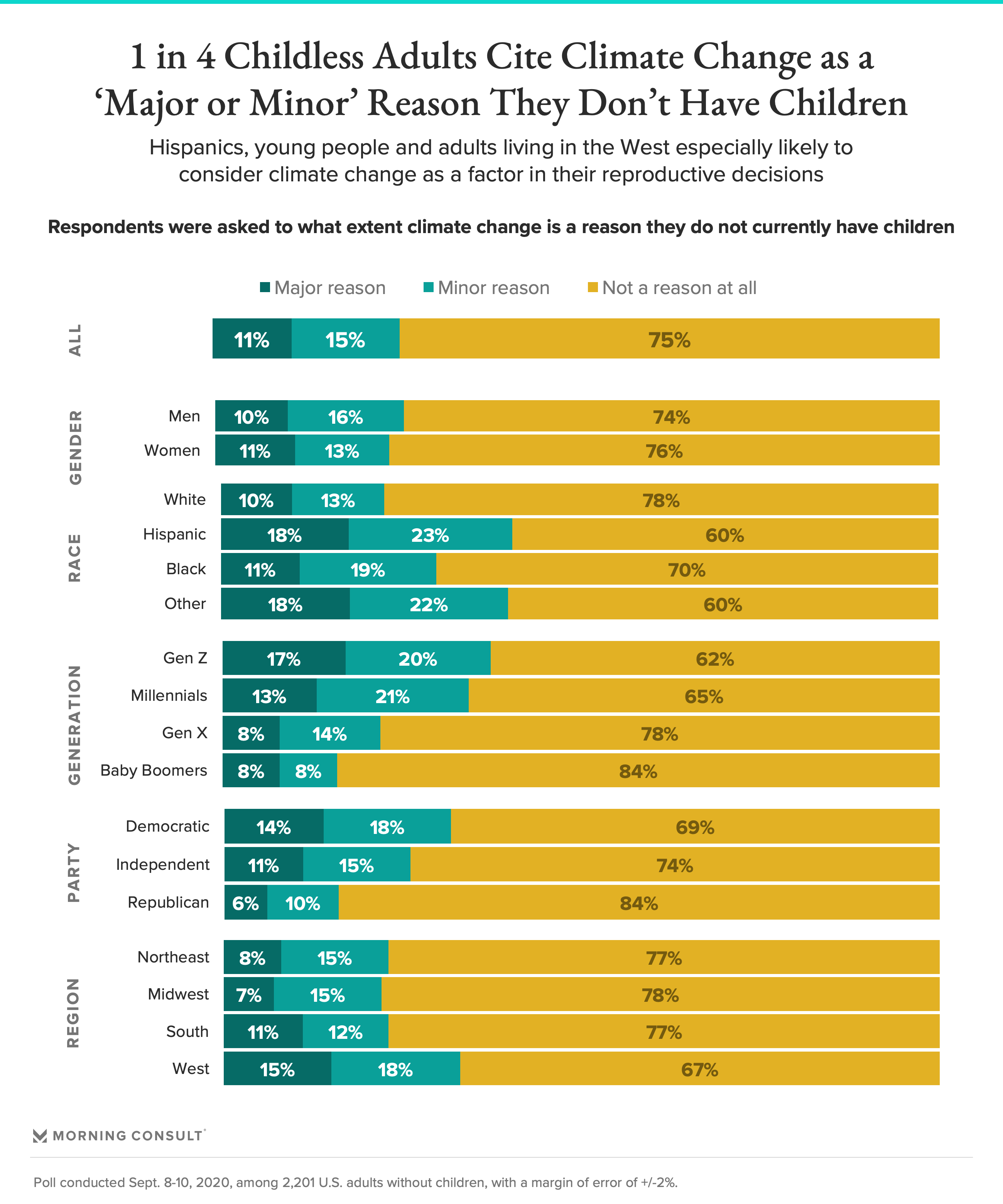

It’s one of the most private decisions, even as the public discussions on having children in the face of an uncertain climate future tend to be contentious for a host of reasons. But that conversation is again front and center in the United States, where a new poll of childless adults finds that one in four say climate change is indeed a factor in their family planning.

The Morning Consult poll, released on Monday, also noted that the trend is especially true among some minority groups in the U.S.

“Childless Hispanic respondents were especially likely to say their concern for climate change has impacted their plans, with 41 percent saying it is a major or minor reason they don’t have children,” said Lisa Martine Jenkins in a summary of the findings. “Thirty percent of Black respondents and 23 percent of whites said the same.”

There was a notable geographic difference in the findings too: a third of Americans living in the West, where wildfires and other disasters are linked to climate change, said climate factors into their decisions about children. That’s 10 percent more than respondents in the South and Northeast, and 11 percent more than in the Midwest. Politically, twice as many Democrats say it’s a factor than the more conservative U.S. Republicans do.

The poll was conducted in early September. It includes 4,400 responses on a range of questions about parenting, with a special focus on how the COVID-19 pandemic is shaping the decisions of millennial adults long confronted with economic and other challenges. Half of the respondents were childless adults, for whom the poll has a margin of error of 2 percentage points.

“Baby boomers were less likely (16 percent) than members of other generations to cite climate change as a reason for not having children, perhaps unsurprisingly: for most, the phenomenon was not part of the popular conversation when they made decisions about whether or not to have children,” Jenkins said. “However, for both Gen Zers and millennials, the issue seems more salient, with 37 percent and 34 percent, respectively, saying it is a major or minor reason they do not have children.”

In recent years, the topic of children comes up among climate scientists who are parents like Kate Marvel or Eric Holthaus, author of a new book, “The Future Earth: A Radical Vision for What’s Possible in the Age of Warming.” It’s the less-optimistic motivation behind BirthStrike in the UK and other movements that advocate remaining childless. It’s the reason that Roy Scranton, an American academic and author, said he cried twice when his daughter was born.

“First for joy,” he wrote in a 2018 essay. And then for sorrow: “My partner and I had, in our selfishness, doomed our daughter to life on a dystopian planet, and I could see no way to shield her from the future.”

Decisions about climate and children exist in a complex web of experience and emotion, as organizations including Project Drawdown – an advocate of girls’ education and smaller family sizes – have noted in the past.

“The topic of population also raises the troubling, often racist, classist, and coercive history of population control. People’s choices about how many children to have should be theirs and theirs alone,” the project says. “And those children should inherit a livable planet. It is critical that human rights are always centered.”

Still, Project Drawdown insists that future climate solutions have to consider “how many people will be eating, moving, plugging in, building, buying” because population is interlinked with emissions through fossil-fueled production and consumption. This new poll shows just how much that future is shaping decisions on children.

Did you like it? 4.7/5 (20)