Climate justice is more than just another catchy concept. It is quickly gaining global prominence and changing trajectories of climate action. Still, questions regarding what a climate just future might look like and how we can get there remain as pertinent as ever.

The basic premise of climate justice is that climate change is an ethical and political issue because underprivileged people and underdeveloped nations that are least responsible for climate change are often those who will suffer from it most. The math is simple: 10% of the global population are responsible for 50% of emissions, mostly located in the global north. Income, race, gender, health and age are other increasingly recognized factors that impact people’s ability to deal with climate variability.

Some of the early considerations of climate justice date back to the Kyoto Protocol and its principle of common but distributed responsibility, where developed nations had to limit emissions while supporting climate change mitigation in less developed ones.

Since then emissions by China have risen sharply even as climate justice ideas began gaining supporters at COP conferences and elsewhere, leading to the formation of the Climate Justice Network in 2009. Most recently, the climate justice movement has seen protests led by the young Swedish activist Greta Thunberg while a People’s Demands for Climate Justice declaration has been signed by almost 300 000 people, calling governments for 100% renewables by 2030 and banning all future fossil fuel developments.

Today, thanks to the climate justice movement, there is much wider attention paid to the unequal impacts of climate change globally and across generations, as well as varying vulnerabilities in regional and local contexts. All of these are now real concerns of decisionmakers worldwide. Societies are also starting to embrace the ever-increasing complexity of climate challenges.

However, knowing who is actually most in need of help and how to allocate resources so they can improve the climate resilience of a society doesn’t always translate into meaningful action. A more careful look at the distribution of heat islands, green areas and pollution hubs across a city or at how to provide equal access to water in times of droughts often exposes a simple fact: people with more money and power are always better prepared and better protected, yet they are often less interested in challenging the status quo.

Inequality and climate change remain tightly linked challenges as many countries are going to realize in coming years. Very often real climate action will not be about trendy green tech trends but about measures to reduce inequality within cities. But that is something less shiny and harder to sell to investors and those in power because many of them still often see climate action as just another economic opportunity on the horizon.

Thus, climate justice can lead to a clash of cultural perspectives and uneven distributions of risks that might aggravate the situation. Debates may also give rise to questions such as who is responsible to whom and for what. How do we approach the issue of China’s government executing climate actions at home even while it is heavily funding fossil fuels and polluting industries elsewhere? Can we hold the country responsible for its share of harmful actions when much of its emissions are coming from goods produced for the consumerist societies of the west?

And what about conflict metals used to produce EVs, such as lithium mining that poisons rivers, pollutes the air and depletes groundwater sources in Chile, Bolivia, and Tibet? Can we truly consider expensive EVs that are affordable only to a few to be a sustainable means of transport, especially if they cause identifiable cases of suffering and environmental degradation in other parts of the globe? Likewise, even if climate debts are paid to developing nations through climate finance schemes, won’t such infusions of money influence local politics and future choices negatively?

These are hard questions that climate justice activists need to ask. Yet the fact remains that any climate injustice comes at a price we will ultimately have to pay together. While contemporary climate injustice is particularly visible in times of disasters when the most vulnerable also face the biggest challenges in recovering, there is more to the story.

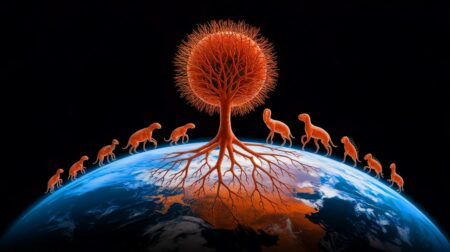

One of the most critical facets of climate justice is how it reveals that our world is tied in intricate connections across space and time. By helping people on the other side of the planet to avoid the degradation of an ecosystem there actually means helping ourselves.

Similarly, no urgent action will save us if it is for the temporary benefit of the few, especially if they prefer to remain ignorant of their dependence on others for their privileges. New climate realities will affect us all: with wars, floods, the spread of diseases and natural disasters that will make Earth less habitable even to those who are well-off and better protected from the extremes.

As we are wiping species out across the globe, we are ending life on the planet as we know it. Yet if we understand our ultimate interdependence and address the issues accordingly, we can still make the planet more habitable for us all.

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (25)