Universities, governments, faith groups and others are changing their investment policies to better align with Paris Agreement climate goals, but they’re also doing so to limit the risk of financial exposure — and that’s been met with political pushback over stranded assets, particularly in Britain and the United States.

The most recent example comes from HSBC, the banking institution based in London. Stuart Kirk, global head of responsible investments for HSBC, presented a talk earlier this month called “Why Investors Need Not Worry About Climate Risk” at a Financial Times Moral Money summit. In it, he dismissed the climate threat by saying it was just another hyperbolic “sky is falling” scenario, similar to Y2K fears at the turn of the millennium.

“The more we’re ‘doomed,’ the higher prices go,” Kirk said, while presenting data framed to demonstrate that the more that public discourse focuses on climate catastrophe, the “higher and higher and higher risk assets go.”

Kirk’s remarks drew widespread media coverage from news outlets including the New York Times, which then published a May 27 article on how oil and gas interests, alongside politicians, are placing pressure on firms like BlackRock in order to curb their responsiveness to climate when managing assets and evaluating financial risk.

BlackRock holds $259 billion in fossil fuel-invested client assets, with significant holdings in Exxon Mobil, ConocoPhillips and Kinder Morgan, among others, the Times reported. BlackRock also issued a May 2022 investment stewardship policy statement that places limits on the types of climate-related proposals it will consider from its stakeholders.

“We are not likely to support those that, in our assessment, implicitly are intended to micromanage

companies,” the statement said. “This includes those that are unduly prescriptive and constraining on the decision-making of the board or management, call for changes to a company’s strategy or business model, or address matters that are not material to how a company delivers long-term shareholder value.”

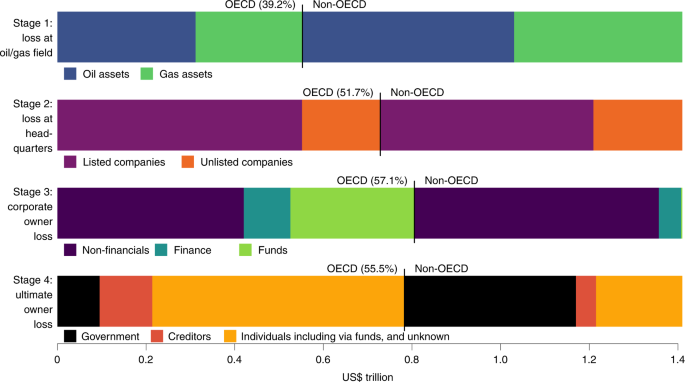

It’s a troubling trend, considering what’s at stake in moving the global community forward in an energy transition that leaves fossil fuels behind. New research, from a team led by economist Dr. Gregor Semieniuk of the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and British-based colleague Philip B. Holden, assessed the potential losses associated with stranded assets in the oil and gas sector and found that US$681 billion could affect financial companies, with $1.4 trillion in stranded assets overall.

“The U.S. and UK financial sectors display much larger losses than other countries,” the authors said in the paper, published last week in the journal Nature Climate Change. The models were based on a moderate warming scenario of 3.5 °C during this century.

Among their calculations, the researchers note that private persons own over half the risk and losses would exceed equity in some 239 companies, leaving them technically insolvent. That means that multiple players, including municipalities and people with pension funds invested in BlackRock and other financial firms, are potentially exposed to future climate losses.

Meanwhile, politicians who oppose climate action and the financial institutions themselves appear to be moving even further from the consensus on an urgent energy transformation needed to cut carbon emissions.

Kirk has been suspended for his remarks pending an investigation, according to the Financial Times on Sunday, in a piece that explores insights drawn from the controversy over the speech and its assessment of “the intensity of the ESG culture war.” That environmental, social and governance investment (ESG) war isn’t new but it appears to be entering a new phase at a critical time for evolving climate policy.

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (22)