Germany has only two aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES) systems in operation, one in Bonn and one in Rostock, but a new study of the climate-friendly ATES technology finds that more than half the country could benefit in the future.

An ATES system relies on shallow groundwater sites to transfer and store excess heat or cold, depending on the season. The water held underground can then be pumped up as needed, in keeping with the heating or cooling demand in connected buildings.

There are currently 2,800 such systems across the world, most of them in the Netherlands—the nation that has led the way on ATES technologies. Sweden has about 220, while Belgium has 30. They’re typically used to deliver heating and cooling to large buildings, like hospitals, universities, or airports.

In the United States, Stockton University installed the nation’s only campus ATES system, assisted by IF Technology and Underground Energy geothermal engineers. The Stockton system, above, powers its air conditioning. Increasingly, ATES systems are used in residential buildings like the new Brink Tower in Amsterdam.

While Germany is slower to adopt the technology, scientists from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) have mapped the entire country to demonstrate how low-temperature (LT) ATES systems could dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions associated with heating and cooling, which accounts for 30% of Germany’s energy consumption.

These systems differ from high-temperature ATES, which can handle waste heat from industrial processes and power plants as well as solar thermal energy, but have significantly different requirements because of their higher temperatures and increased storage depths.

The KIT team studied only the LT use in individual buildings or complexes, and said deploying ATES could reduce these building-related emissions by up to 75% when compared with legacy heating and cooling systems. Their paper was published recently in the journal Geothermal Energy.

They based their findings on calculations derived from climate and hydrogeological data, and demand estimates. “Besides climatic factors, other aspects such as set point temperatures, internal heat gains and building insulation also significantly influence the heating and cooling energy demands,” the authors note.

“The country-wide scope of our study, however, does not enable us to easily integrate this kind of detailed building-specific information. We therefore use degree days to obtain a proxy for balanced heating and cooling demands, which is not limited to existing building stock and settlement areas.”

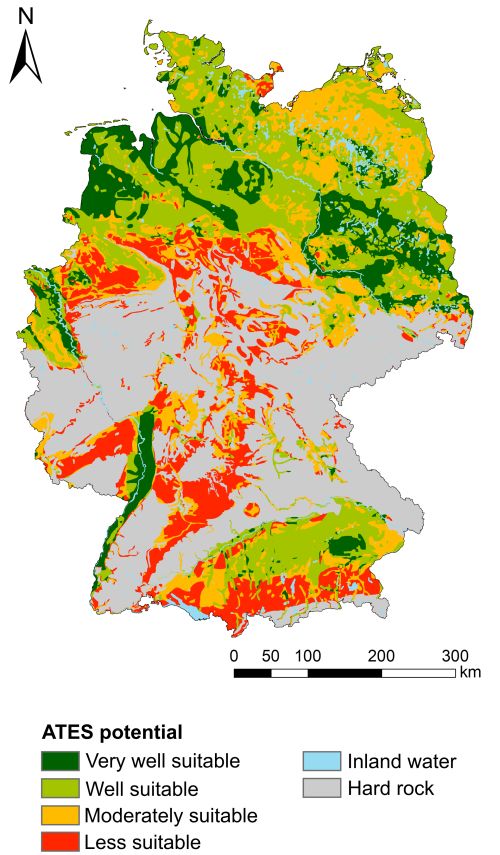

As a result, the 54% of the country deemed suitable for future ATES use (including those that become so through 2050) is found primarily in three geographical regions of the North German Basin, the Upper Rhine Graben and the South German Molasse Basin.

One regional factor that affects Germany’s potential use of ATES is the type of rock. In about 35% of the country, either hard rock or inland water surfaces mean that ATES systems can’t be used. However, the scientists expect a 13% increase in where ATES can successfully be deployed by 2100.

On the other hand, water protection zones (as with drinking water) may limit the use of ATES systems by 11%, the authors note.

“Still, our study reveals that Germany has a high potential for seasonal heat and cold storage in aquifers,” says co-author Rubin Stemmle.

Did you like it? 4.6/5 (20)