New research suggests how we might try enacting carbon taxes.

We might need to change our carbon-pricing method

Increasing carbon taxes over time is viewed as a common-sense solution to emissions. New research suggests how we might try doing it. A paper published in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences outlines a path for starting with high carbon taxes, increasing them slightly over a decade, and then letting them go down slowly.

The new research clashes with previous models of climate and economy, which mostly suggest initially low carbon taxes that grow over time. Dealing with climate damage doesn’t cost much now and will cost just a little bit more in the future (and even less with better technology), the thinking goes, so we should distribute costs accordingly.

However, growing climate impacts across the globe, paired with revised projections, paint a different picture: humanity may well be heading straight for an unstable and largely uninhabitable “hothouse Earth”. This realization forces scientists to rethink their scenarios of the future and to start reconsidering actual risks and uncertainties.

A newly introduced EZ-Climate model takes into account costs related to climate uncertainties and offers novel valuations of climate risks. This was possible due to improved probabilistic understanding of potential losses and damages related to climate change.

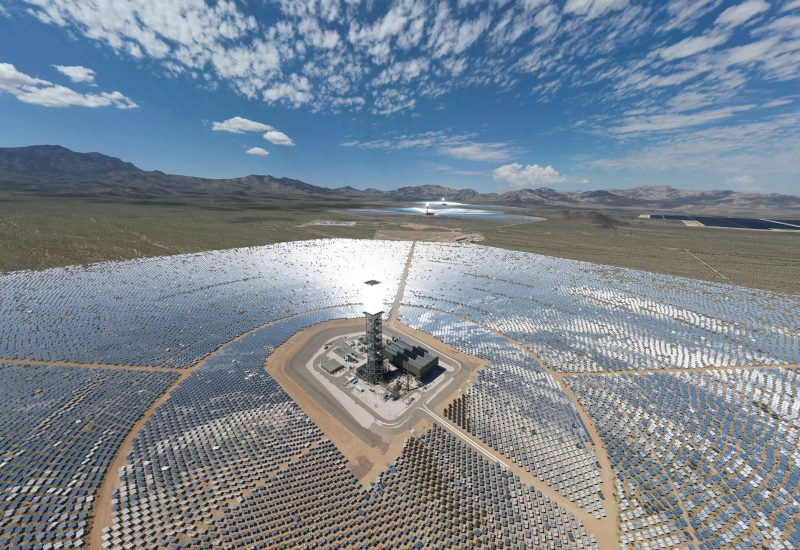

The modeled tax dynamics make electric vehicles, solar energy and other green technologies much more attractive because they speed up decarbonization and a transition to cleaner economies. Higher taxes would also provide a buffer against disasters, safeguarding society from economic shocks connected to climate variability, the researchers argue.

Once we stabilize the climate, however, we can let the carbon tax fall slowly, they say.

The researchers say the amount of the required carbon tax should depend on particular circumstances. Different EZ scenarios suggest a price range between $100 and $200 per ton of CO2, which is a lot higher than in most countries across the globe today.

Robert Litterman, a co-author of the study, notes: “To me the most surprising result of the research was how quickly the cost of delay increases over time.”

Although many may see the results as way too costly, it pales in comparison with the $135 to $5,500 per ton of CO2 rate by 2030 suggested in last year’s IPCC report if we are to stay below 1.5 ºC warming. Unlike the new study, though, the IPCC estimate suggested growing taxes over time, amounting to as much as $27,000 per ton of CO2 in 2100.

Both studies agree that the further we delay climate action, the greater the costs associated with climate change will be. One year delay in introducing the relevant climate tax can lead to $1 trillion’s worth of climate impacts. The new study’s authors point out that Green New Deal policies and costs, suggested by several presidential candidates in the upcoming U.S. elections, could be close to the true price of climate action required.